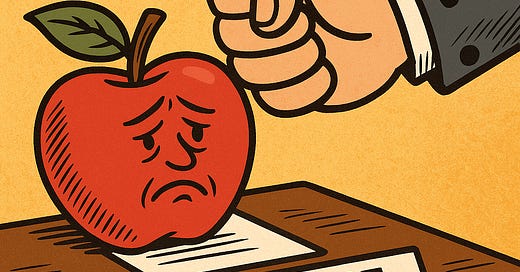

Trading Experience for Economy: The Devaluation of Adjunct Professors

Worshipping the almighty dollar while ignoring student education

In recent years, a quiet shift has been unfolding on some university campuses — one that undermines educational quality under the guise of cost-cutting. I’ve seen it firsthand. Once valued for our decades of professional experience and academic accomplishment, adjuncts like me are being edged out — not because graduate students offer better instruction (they don’t), but because they are cheaper.

The economic logic is simple: graduate students already receive stipends and tuition waivers, so assigning them classes is a marginal additional cost. From a budgetary standpoint, it might seem like a win. But from an educational perspective, it is a loss, and students are paying the price.

I bring more than 40 years of real-world experience and the requisite degrees to my courses. I have navigated the complexities that students will one day face in their careers. I offer more than lectures; I offer insights forged through decades of practice, mistakes, and hard-earned victories. My students don’t just learn theory—they understand how the theory collides with reality.

A graduate student, however bright or motivated, simply cannot replicate that depth. Most have little to no professional experience outside the classroom. They have not managed projects, led teams, negotiated contracts, or dealt with the unexpected challenges that arise daily in the professional world. Their instruction, however earnest, tends to reflect the narrow lens of academia, not the broader, messier landscape of actual practice.

Universities seem to have forgotten that education is not just about transferring information; it’s about preparing students for the real world. And the real world is not a seminar room.

Of course, the rise of graduate student instructors is not their fault. They are doing their best with the opportunities afforded to them, and many will grow into excellent educators and practitioners. However, asking them to lead classes meant to bridge academic theory and professional practice, while pushing out those who have already walked that bridge, is misguided.

The broader trend reflects a troubling shift in higher education. Administrators view instruction increasingly through the lens of financial efficiency rather than educational excellence. Adjunct faculty, already underpaid and often treated as expendable, now find fewer opportunities to share their expertise. Meanwhile, students are charged ever-higher tuition fees for a diminished product.

This is not just an economic issue; it is a philosophical one. Universities must ask themselves: What is the purpose of higher education? If it is merely to confer degrees at the lowest possible cost, then sidelining experienced instructors in favor of cheaper alternatives might make sense. But suppose the goal is to truly educate, challenge, and prepare students for life's complexities beyond academia. In that case, seasoned educators' value cannot be easily dismissed.

There is also the issue of mentorship. Students benefit enormously from instructors who have real-world insights, can offer career guidance grounded in experience, and can mentor them academically and professionally. Graduate students, admirable as they are, simply have not lived enough of that professional journey to serve as effective mentors.

Moreover, the sidelining of adjuncts sends a demoralizing message to those who have dedicated their lives to public service, business, law, education, and other fields. It tells us that our experiences, insights, and hard-earned wisdom are less valuable than a line item on a budget spreadsheet.

If universities prioritize short-term savings over the long-term value of education, they risk producing graduates who are less prepared, less capable, and less competitive in the professional world. In a time when higher education faces increasing scrutiny over its cost and relevance, this is a dangerous path.

Students deserve more than instructors who are learning alongside them. They deserve mentors who can say, “I’ve been there, and here’s what you need to know.”

We must advocate for a rebalance. Universities should not replace experienced adjuncts with graduate students simply because it is convenient. Instead, they should invest in a faculty that reflects a blend of scholarly achievement and real-world wisdom. Students are entitled to an education that equips them not just to pass exams, but to succeed beyond the campus gates.

Trading experience for economy may look smart on a balance sheet. But in the lives and futures of students, it is a loss that cannot be recouped.

The time to reverse this trend is now. Universities must recognize that proper education cannot be done “on the cheap.” It requires investment in people who have walked the walk, not just talked the talk. It requires valuing practitioners who bring the messy, complicated, invaluable lessons of the real world into the classroom.

This trend also reveals a deeper cultural problem: the erosion of respect for expertise that can’t be quantified in academic citations or measured by standardized rubrics. Universities are increasingly obsessed with metrics — credit hours delivered, student evaluations, research output — while disregarding the intangible but vital value that seasoned professionals bring to the classroom.

This is a fundamental misunderstanding of what makes education transformative. Numbers matter, yes. But so do stories, judgment, and the kind of nuanced understanding that only comes from decades of work.

There’s also a ripple effect. When universities undervalue experience, they send a message to students: that lived knowledge and professional acumen are secondary to theoretical familiarity. This distorts students’ expectations of the workplace and undercuts their preparedness. It subtly shifts higher education from a launching pad into the real world into a cloistered echo chamber where theory reigns unchallenged.

Worse, it de-professionalizes teaching. Instead of being a calling or a craft, it becomes a budget item to be trimmed. Faculty are no longer mentors or masters of their fields — they’re placeholders. This devalues not only the teaching profession but also the student experience.

Rebuilding respect for practitioner-educators isn’t just about saving jobs; it’s about restoring the integrity of higher education. A university’s responsibility is not just to its balance sheet but also to its students and to society. Producing thoughtful, capable, and adaptable graduates requires more than cutting costs. It requires a commitment to quality, mentorship, and the kind of learning that lives on long after the diploma is framed.

We’re not asking for charity. We’re asking universities to honor their mission — to educate fully, meaningfully, and responsibly. That begins with recognizing the irreplaceable value of experience in the classroom.

Professor Mike teaches justice studies at a well-known university. He has also taught counterterrorism and global security, focusing on contemporary threats and international crisis leadership.

In case you missed it:

"the erosion of respect for expertise" has more than one precedent in the history of totalitarian politics. In fact any sore of information as well as the ability to use it can be seen as a challenge to revolutionary authority - a return to status quo ante, which a revolution needs to prevent. I often think of the Maoist "cultural Revolution of the late 60s and 70s when students replaced professors, hospital orderlies and janitors took over from doctors and nurses and most persons of skill or knowledge or authority were actually punished - and worse. I know people who went through it. Trumpism is a similar attempt to replace a government, a culture, a legal and educational and health care system and sell it as freedom - and we see it in the attack on education, on medicine, on science, on information, on freedom of choice and equal protection under the law. As many as two million Chinese may have died in that decade long experiment. It involved widespread violence and persecution and although one has to be careful with analogies, I expect something similar if we cannot stop the Trump Gang and its barbarian revolution.